Contributions to Regenerative Agriculture from African Americans

Although regenerative agriculture looks to be a hot topic lately, it’s a practice that has been in use on farms around the world for hundreds and thousands of years. Undoubtedly, a handful of current advocates will get credit for bringing discussions around regenerative agriculture back to the climate action table.

However, we shouldn’t forget those who promulgated ideas of sustainable and regenerative agriculture long before it was trendy. Many people from around the world have been using agricultural systems and practices that replenish the soil, create healthier air, support cleaner water supplies, and lead to flourishing ecosystems.

In honor of Black History Month, I wanted to call out and amplify the contributions of a few of the African American leaders who have played an integral role in regenerative agriculture in recent history.

George Washington Carver

I stumbled upon Carver’s story through The Little Plant Doctor, one of the many gardening and plant-focused picture books I checked out from the library for my boys. Attracted to the wonders of plants from a young age, George Washington Carver pursued his passions throughout his life.

Carver was born into slavery and lost his mother to slavery supporters at a very young age. His owners raised him and he received more education than many other slaves, but he still faced oppression and inequality throughout his life.

As a child, Carver curated gorgeous gardens. He grew his own gardens and also helped neighbors revive and grow their gardens. His exceptional knowledge and ability to heal dying plants in his community earned him the title of The Little Plant Doctor.

After a variety of travels and jobs, Carver earned a position at Iowa State University in their agricultural department. He became well-known for his sustainable agriculture work that promised to help farmers grow more successful harvests and put more healthy food on people’s dinner tables.

A few years into his career at Iowa State University, Booker T. Washington called to request that Carver join the faculty at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The Tuskegee Institute was a school specifically for Black students to advance their education, and Washington hoped that Carver would start an agriculture department at the school. Carver accepted and headed south.

During his time at Tuskegee, Carver explored all sorts of ways to better utilize farmland, diversify crops, naturally care for the soil, and make the most of the resources available to farmers, all without much of a budget to spend. Carver advocated for the use of compost to feed the soil while letting nothing go to waste. He also promoted crop rotation and biodiversity.

Most notably, Carver studied peanuts and recognized that this legume puts nitrogen back into the soil. Many crops deplete nitrogen reserves in the soil, and rotating peanut crops with traditional crops, like cotton, help revive unhealthy soil.

With his research and knowledge on the topic, Carver published a book about successfully growing and using peanuts in over 100 different recipes, intending to create a larger market for peanuts. He wanted to allow farmers to grow peanuts to replenish their soil and also sell the crop or a profit.

We continue to recognize Carver’s expert botany and horticulture skills today and utilize his great contributions to the sustainable and regenerative agriculture space.

Booker T. Whatley

A student of George Washington Carver, Booker T. Whatley followed in his mentor’s footsteps. He made great strides in supporting small farmers and creating new ways to sustain local agriculture markets. He created a very popular guide for small farmers in which he explains how to set up a profitable small firm in spite of the growing power and influence of large, commercial farming operations.

In his guide called How To Make $100,000 From a 25-acre Farm, Whatley encourages farmers to plant a variety of crops in order to produce income streams from harvests throughout the year. For example, he suggests living within 40 miles of a metropolitan area to reduce travel expenses and increase the market for the available sale of harvests. He highlights the value of having plants and animals together on a farm, as their presence benefits each other. His concepts help drive a financially successful farm and also reflect best practices of sustainable agriculture such as crop rotation and reduced carbon emission from transportation.

Notably, Whatley encouraged farmers to run their farms on a membership program whereby customers paid a recurring fee to receive a portion of the farmers’ harvests. This was a novel idea at the time, but it became the foundation for modern-day Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) programs.

CSAs create a more sustainable source of income for farmers. They allow farmers to share the benefits of bountiful crops and the risks of poor harvests with their customers. Today, they are an important component of sustaining small and local farmers who play a big role in regenerative agriculture, soil health, and biodiversity.

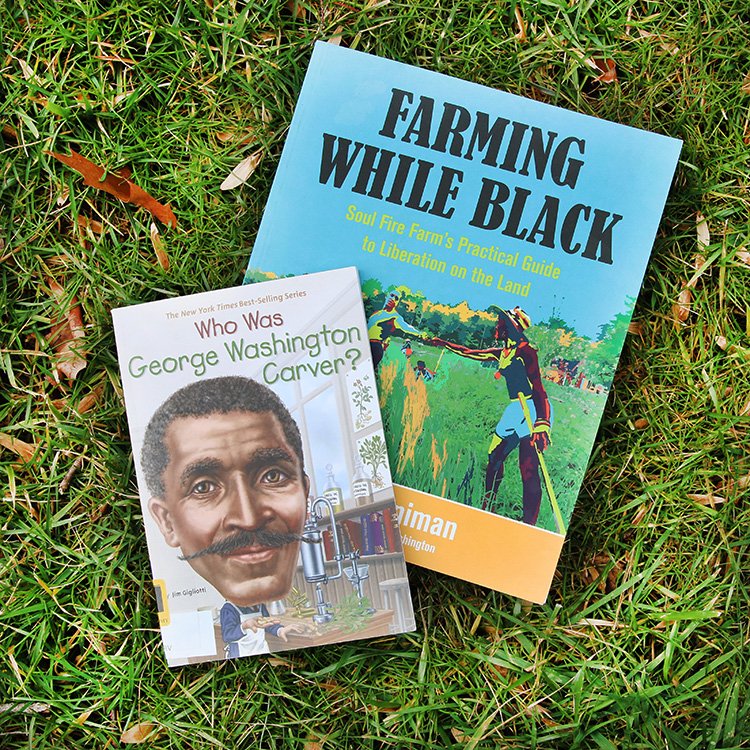

Leah Penniman

Author of Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land, Penniman’s book helps Black people reconnect with the land and start their own farms and growing spaces.

With the help of her partner and several others, Penniman runs a small farm called Soul Fire Farm. They created the farm from an empty plot of less-than-stellar land and with a very limited budget. On the farm, they produce food for their families and the local community, run a sliding-scale CSA for nearby neighborhoods, and host programs to help train Black and Latinx aspiring farmers who want to reconnect with the land.

This book seems to have two main intentions. First, the book offers technical skills to educate Black people about how to start their own farms, though this guide is very detailed and can be used by anyone interested in starting their own sustainable farm or garden.

Second, the book strives to uplift stories of African-heritage people who have advocated for and advanced sustainable agriculture throughout history. Various sections throughout the book discuss how African-heritage cultural and ethnic groups from around the globe, and especially the Caribbean and Africa, have used sustainable habits to foster farming and food production success in their communities for centuries.

I encourage you to buy the book (and support Penniman with your purchase) or check it out from your local library. Read the “Uplift” sections, even if you don’t plan to start your own farm. There are so many interesting stories and skills carried forward from past generations of Black communities globally.

Throughout the book, the author discusses how African-heritage cultures historically discovered, developed, built cultures around, and shared sustainable agriculture practices, traditional and plant-based medicines, special crops, and much more related to farming. As I read, I found myself often thinking “But didn’t non-Black people do that too?” or “Are white people really the only perpetrators of all this cultural and environmental damage?”

In some cases, the answers might be no and yes, respectively. As a white person, it can be a tough pill to swallow. But in the context of this book, it doesn’t really matter if non-Black people made contributions to sustainable agriculture or non-white people perpetrated cultural and environmental damage. That’s not what this book is about.

Among other things, this book is written for Black people about recovering and rising up from the oppression of white people and uplifting the agricultural stories and cultural elements lost through enslavement, oppression, and injustice. The book is a space reserved to serve and uplift those of African heritage, and it’s filling an important void.

Throughout the book, Penniman shares many practical and tactical solutions and guidance that can help people of all backgrounds. The author lays the groundwork in a very accessible way for aspiring farmers and gardeners to practice regenerative agricultural methods on small farms or gardens even with limited budgets.

They Are Not Alone

Carver, Whatley, and Penniman are, of course, not alone in their pursuit of promoting regenerative agriculture practices and connection to the land for Blacks and small farmers generally. As I mentioned above, Penniman shares a host of excerpts highlighting so many more contributions from African-heritage communities in sustainable agriculture spaces.

However, they have and continue to play important roles in building and reviving regenerative agricultural methods that will be integral to supporting biodiversity, reducing carbon emissions, replenishing soil health, and growing food in a way that sustains humans and heals the planet.

I’d love to hear about more Black people who are contributing to regenerative agriculture. I have so much to learn and look forward to being introduced to more people changing the world for the better.

![Green Banking Alternative | Comprehensive Aspiration Review From A Current Customer [2021]](https://www.honestlymodern.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Aspiration-Green-Financial-Services-1.jpg)