Building Community Bike Culture in Car-Centric Cities

Would you love to have stronger community bike culture in your town but can’t imagine anything other than a town dominated by car transport? Community bike culture and the related bicycle infrastructure required to foster a culture of bicycle transportation are a choice, even for car-centric communities… if they are willing to change. Read on to learn more about how the Netherlands transitioned from car-centric cities to bike-centric cities to be one of the most bicycle-friendly places in the world.

This post is part of our series on showcasing family biking as a regular mode of transportation and how it can benefit both people and the planet.

The Netherlands is famous for its bicycle infrastructure and community bike culture. But did you know that bicycle culture was a recent and very intentional decision?

People in the Netherlands have always biked, but dedicated bike roads and bicycle infrastructure are relatively new. In the 1960s, driving was becoming more popular all over the world. But by the 1970s, cars, bikes, and trams crowded the streets of Amsterdam, and it was inefficient and dangerous to travel through the city.

Dutch Residents Chose Community Bike Culture

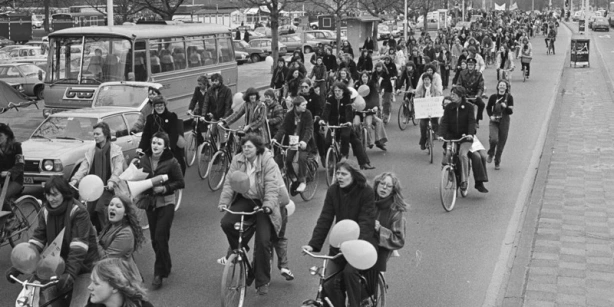

Massive bike protests took place during which people flooded the streets with their bikes. Residents also took up a campaign called ‘Stop de kindermoord’ (stop the child murder). Rather than embracing the car lifestyle and building more roads and parking, the Dutch people revolted and demanded safer cycling.

The transition away from only car-centric transportation routes took a decade of protests to initiate, but the work finally began. It is still in process, though many cities in Amsterdam are now very bike-centric, which makes bicycling through the city more efficient, safe, and enjoyable.

In my small town of Delft, with about 100,000 inhabitants, the beautiful central square was a parking lot as recently as 2003. Many of the businesses and restaurants surrounding the “parking lot” did not want it removed for fear it would lessen their business.

The narrow and historic nature of Dutch streets did not preclude their cities from succumbing to the automobile after World War II. But critically, they've spent the past few decades correcting those mistakes.

— Melissa & Chris Bruntlett (@modacitylife) July 7, 2019

Delft city centre—now mostly car-free—pictured in the 1960s and '70s. pic.twitter.com/ylmcuOoitA

In 2003, however, the city government convinced a few businesses to make patios in the previous parking spaces. Customer activity and business turnout were so much better for these few test spaces, that eventually all the businesses around the square agreed to fully transition the square. Today, it is a beautiful space for people to gather.

While biking is popular here, especially within cities, driving is one of the main forms of transportation for traveling between city centers and urban areas. During a recent ski trip to Austria, almost every third car on the German Highway was a Dutch car. It is a 12-hour drive from the Netherlands to the part of Austria in which we were traveling; the long drive is not for the faint of heart. In short, it was clear that despite the bike-centric culture, the Dutch still use cars for longer transportation.

Creating different travel networks for different modes of transportation

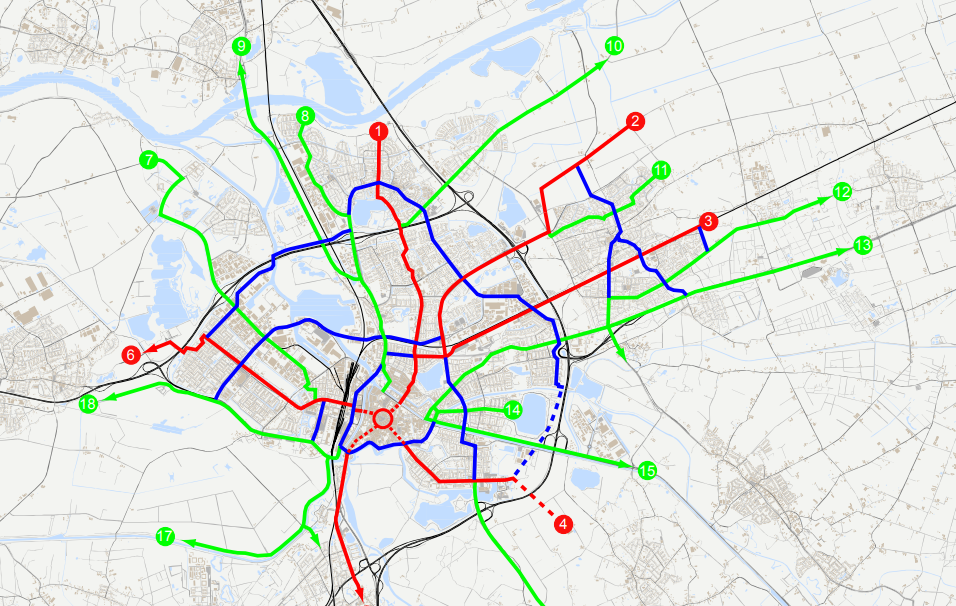

So what is the Dutch philosophy of transportation and how did they develop a strong bike culture? How do they support bikes, trains, and trams, as well as the car? Among other things, they use a method of disentanglement, a principle that separates different types of transportation into their own paths and networks so cars, bikes, and pedestrians aren’t sharing the same roads and pathways with each other.

Car-centric highways go around town instead of through it

First, Dutch city planners make it difficult for cars to drive within city centers but easy to drive between cities. Most Dutch highways pass around the outside of towns (instead of through their centers, like many highways in the United States). Cars can travel more freely in the open space between towns.

To enter the town and move around within the more urban areas, one must park and walk or bike. Many people who commute into the city take the train. They bike to the train station in their town, lock up their bike, get on the train, and then have a second bike at their train destination to bike to their work. These are not expensive bikes but rather beat-up commuter bikes that may not look pretty but get the job done.

Design certain roads to serve bikes or pedestrians better than cars

City planners also design roads differently based on the purpose of each road. Main roads intended to connect local places might be designed as bike-only or bike-centric roads. These types of roads or pathways discourage car traffic by providing fewer lanes for cars, giving bikes priority over cars on a shared roadway, or simply prohibiting cars from using these roads. They also encourage more people to ride bikes because the bike paths are the most direct (and fastest) route to their desired location.

Car travel is slow on bike-centric roadways

In many cases, when bikes have priority, it makes car travel (when there are car lanes available) quite slow, an incentive to avoid these roads and use the car-centric roadways instead. Bikes might ride side by side near cars in dedicated bike lanes. And if you are following teenagers, you may get stuck behind a group of 5-10 meandering friends.

There are other roads where the car is the priority. These roads usually cut through town but have few ways to enter neighborhoods. There may be a red, paved, bike road running next to it, separated from the car lane by a curb or line of parked cars. You never see bikes right next to a car on these types of “car-first” roadways.

Cul-de-sacs reduce card traffic but also limit bike traffic and walking

The United States also tried to limit car traffic in neighborhoods, but instead of reducing ways for cars to enter the neighborhood roadways, they made the cul-de-sac. The idea is to make it so confusing to navigate a neighborhood that only residents can find their way and other cars stay out.

However, the design also made it very impractical for pedestrians and cyclists. For example, in my in-law’s neighborhood in Southern California, we can see Target just at the top of their cul de sac. But to walk there takes 30-40 minutes. Kids do not want to walk that far, even if I bribe them with a snack. It is much faster to drive. So we hop in the car and drive, even though it’s really close by.

In our town in the Netherlands, we also live in a residential area. It takes about 15 minutes to walk to the closest grocery store, but it is a 2-minute bike ride. Both of these are much more doable than the walk to Target in my in-laws’ community. Additionally, the ride to our grocery store is almost completely on bike-only paths or in our neighborhood, where cars go slowly. They drive slowly because they know kids are riding bikes.

Bike roadways that provide lifestyle purpose

Furthermore, city planners intentionally build bike paths that all go somewhere meaningful. Instead of simply riding for fun out on nice country roads, riding on bike paths connects people to places like the grocery store, the sports field, and the park. Bike roads also cut through parts of town like green spaces where cars cannot drive. This makes biking to places faster and more enjoyable.

Because various roads have specific purposes, we have an incentive to use different routes to get to the same location depending on the type of transportation we are using. When we ride our bike, we might get more of a straight line path to our destination, whereas if we drive the car, we might have to swing out a bit in more of a circle shape.

Separating bikes and cards makes both trips faster

While this seems like it would make driving take longer, it is also faster for cars. The car needs to drive a further distance, but it takes less time because the road is less congested. Bicyclists and public transportation riders use other roads, and more people take bicycles and public transit because they are safe, comfortable, and more efficient. So, in the end, everyone is happy.

Car-centric cities can transition to bike-centric cities

Cities that aren’t currently built with bike-centric or pedestrian-centric infrastructure don’t have to rely on cars forever. Many cities in the Netherlands have led by example to show that a transition to bikes, walking, and more public transit is possible and has many positive outcomes for the people, the planet, and the communities overall.

Could your city transition to a more bike-centric culture with changes to the infrastructure? Learn more about the Netherlands in this video.

If you like this post, you might also like

Car-Free Transportation for Families: Our Suburban Bike-Centric Life with 3 Kids

15+ Benefits of Family Biking For People & the Planet

Can You Take a Family Roadtrip in an Electric Vehicle?

About the Author

Robyn Chevalier Hall is a California girl who has called Europe home for five years. She currently resides in the picturesque city of Delft, Netherlands, where she is thrilled to use her bike as her main means of transportation. In her spare time, Robyn can be found reading, gardening, cooking, or running. Throughout her career, she has worked in various roles, including a teacher, a mom to three kids, and nonprofit leadership.