Why Social Enterprises Should Invest In Their Missions and People

Why do we task non-profits with solving immense challenges like poverty, hunger, and public health yet we suffocate them with limited resources and a fraction of the opportunities for growth and development available to for-profit entities?

I think we’re beginning to make strides, loosening some of the double standards applied to entities doing service for others, but we still have a long road ahead of us. Read on for more about the major disadvantages handcuffing charitable organizations and one way we’re giving social justice enterprises a fighting chance.

If you had a world-changing idea that you thought could benefit the lives of hundreds, thousands, or millions of people around the globe, would you invest in it?

Would you hire the best minds to work with you, and pay them well enough to make it worth their while? Would you invest time and money building the idea over time, honing your strategy and creating opportunities to scale or would you stick to ‘small’ and play it safe?

Once it was ready for the world, would you post flyers about it on street poles or would you shout it from the highest rooftops? Would you stick to a small budget or would you solicit investment capital to help build your brilliant idea into something big and beautiful?

The type of legal entity you choose will likely dictate this decision, if not driven by your own perceptions, at least influenced by the double standards of societal pressure. If you elect to organize as a for-profit entity, get ready to invest, develop and go big or go home. If

Societal Expectations About Investing Handcuff Non-Profit Enterprises

I hope this post makes you rethink how you spend and share your money. I hope this post makes you stop and reflect on how you’ve thought about charities and philanthropy in the past. I hope this post even makes you a little bit angry.

Why?

We offer the fewest resources to and set the most crippling expectations for the organizations tasked with solving some of the world’s largest problems. Simultaneously, we give immense freedom and high levels of risk tolerance (aka. flexibility for failure) to the giant corporations trying to sell us more junk.

In his Ted Talk, Dan Pallotta articulates these arguments far better than I do, so have a listen.

To summarize, Pallotta highlights five aspects of investment historically unavailable to non-profits due to social stigma.

Compensation | We don’t allow non-profits to invest in their people and pay employees competitively. Consequently, too much top talent heads straight into the for-profit world because it makes sense for so many reasons. As an example, Pallotta describes how a Stanford MBA can leave business school and, within ten years, make $400,000 in a big company. Alternatively, that person could make $84k as the CEO of a hunger nonprofit. This creates a mutually exclusive choice to either “do good for their family” or “do good for the world”. He further describes why the MBAs make this choice and how it plays out:

“Some people say this is because those MBA types are greedy. Not necessarily. They might be smart. It’s cheaper for that person to donate $100k every year to the hunger charity, save $50k on their taxes… now be called a philanthropist, probably sit on the board of the hunger charity and indeed probably supervise the poor SOB who decided to become the CEO of the hunger charity, and have a lifetime of this kind of power and influence and popular praise still ahead of them. ”

Even worse, we celebrate the CEO making $50 million a year selling violent video games to children while demonizing the CEO making $500,000 working to cure children’s cancer. This just doesn’t make any sense and, understandably, drives away many otherwise interested and capable people from taking on unforgiving careers in the non-profit sector.

Advertising & Marketing | How do we expect our non-profit entities to raise money for their programs when we hardly allow them to ask for it or invest in telling us stories about what they do and why? We don’t allow our charities to invest in fundraising, advertising, and marketing to grow their reach, share their message, and spread the word about all the good work they are doing.

It’s no surprise then that we spend only about 2% of GDP on charitable causes when we are constantly bombarded by advertisements from for-profit entities to spend our money on their wares and services instead. Maybe if we didn’t demonize non-profits for spending money on advertising and fundraising, they could compete with for-profit entities for our dollars and our attention?

Lack of Risk Tolerance in Pursuit of Revenue | High risk bears high reward, right? And low risk, while promising limited downside, also drags along with it an almost guarantee of low reward. How do we expect non-profit organizations to effectively take on poverty, hunger, marginalization, and disease worldwide when they’re forced to perform under far more stifling conditions than their for-profit brethren?

We give non-profits little runway for mistakes, failed initiatives or bad investments. Failure is inevitable in pursuit of innovation, so when we prohibit failure, we also lose the space to innovate and develop life-changing solutions for worldwide problems. We need to let charities take risks, try new things, and understand that more of the same and safe predictable solutions will bear more of the same and painful predictable problems.

Lack of Patience for Investment in Building Strategy and Scale | Rome wasn’t built in a day, nor were any of the massive and innovate for-profit entities grabbing ever-more influence and capital in our world today. While we know it takes time to develop real solutions, societal pressures give little runway to non-profits to develop effective and scalable solutions before bringing them to market (i.e. showing tangible benefit to those being served). It’s understandable that donors desire to see the effect of their dollars in the real world, but it’s also short-sighted to let impatience outweigh the need to build something steady, sturdy and impactful.

No Profit to Attrac Risk Capital | We invest billions of dollars each year in new ideas, many of which don’t work out. In exchange for that capital and acceptance of risk, investors receive a return on their investment. Due to the structure of non-profits, we forbid them from having access to this enormous market of financial resources (that often comes with intellectual resources behind the investment). What amount of capital might we see flow into social enterprises if let investors see even a small return on their funding?

If you were a non-profit, would you rather have a one-time $1,000,000 unrestricted donation or a $1,000,000 capital infusion on which you had to provide a 10% return ($100,000) but could turn into $3,000,000 of future donations or revenue? The $1,000,000 capital infusion with a $100,000 investment return still leaves the non-profit with $1,900,000, a $900,000 benefit over the $1,000,000 donation.

While these numbers are hypothetical, returns on private equity investments are massive. These types of private investments are one of the main causes of increasing disparity of wealth as wealth continues to accumulate in the extreme upper echelons of society. Imagine what private equity investors might do with their money if we allowed them to earn returns on and invest in social enterprises?

We would likely need some guidelines and guardrails in place, as well as more voices from those being impacted by the projects at the table. But it would be great if we could put a portion of investment capital to work in a way that helped solve some of the systematic issues that lead to poverty and inequality.

Solve Big Problems with Small Dollars

As a society (the whole darn world “society”), we’ve tasked governments and not-profits with fixing the biggest and nastiest of our problems. Governments certainly have access to a large pool of resources but they’re constrained by their own set of limitations and are out of scope for today’s discussion. For now, let’s focus on what we give to non-profits and what we expect from them in return.

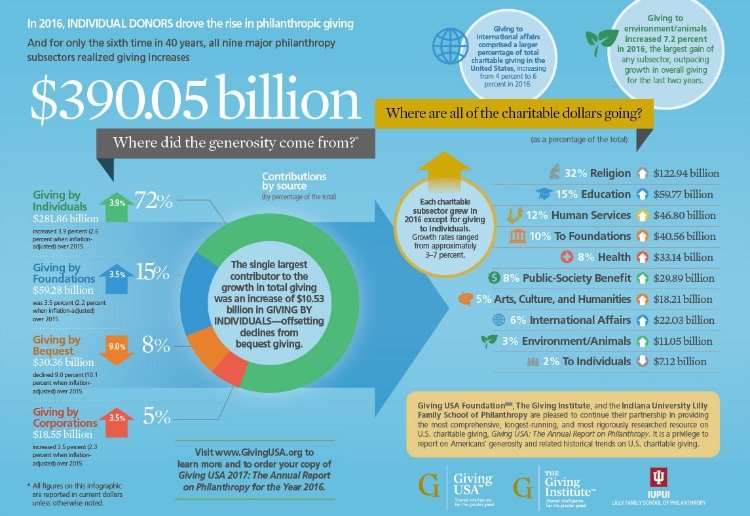

In 2016, non-profits received $390.05 billion in donations, which represents 2.1% of gross domestic product. That sounds like a lot, but compare that to the $12 trillion in revenues earned by the Fortune 500 companies (the 500 largest companies in the US) in the same year. The $12 trillion figure includes revenue from abroad, while the donations include only US revenue, so that distorts figures to a degree. It still, however, represents the funding available to each of the entity classes to invest in achieving their respective missions and non-profits can and do have global reach. In 2016,

Understandably, payments to the Fortune 500 are generally in exchange for some good or service whereas we often recover nothing tangible in return from a charitable contribution. Additionally, a large portion of the Fortune 500 revenue comes from buying things we need, but much of it also derives from buying things we want (and definitely don’t need).

Regardless of the genesis of the funding, we are asking non-profit organizations to solve massive and complex problems (that are far more complicated than the issues many for-profit entities are tackling) with a fraction of the resources. Furthermore, we limit the ability for non-profits to invest in themselves and their missions, use capital markets, compensate employees competitively, and market their message due to cultural expectations of non-profit entities.

Do Away With The Idea of Demonic Overhead

Employee compensation, advertising, fundraising and investment in development all fall under the broad and often demonized category of overhead expenses for non-profits. Understandably, donors want to see their dollars invested in programs, but we forget that the “overhead” to support those programs is a necessary component of the program expenses. Without the people to run then, fundraising and advertising to keep revenue flowing, and investment in bigger and better solutions, we leave non-profits with little power to actually solve the problems they set out to tackle.

We need to change the narrative around overhead or administrative costs and consider a reasonable amount of such costs an investment in the growth and future of the organization. Of course, we don’t want our donation dollars being spent on luxurious travel or capacious meals, but we need to better understand what the ‘administrative costs’ of charitable organizations really entail. We can’t simply ask “What percentage of my donation goes to the cause versus overhead?” This simplistic question assumes that overhead is not part of the “cause” but instead an “enemy of the cause”.

As Pallotta said in his Ted talk, “Our generation does not want our epitaph to read “we kept our charity overhead low‘”, especially if those high overhead costs lead to massive gains in net funding for the causes we hold near and dear to our hearts.

Leah Wise from StyleWise discusses how sites like Charity Navigator perpetuate this flaw in how we assess the quality of non-profit organizations. Charity Navigator measures and reports on the quality of a charity so donors can ensure their donations are given to high-quality recipients. However, Charity Navigator penalizes charities for high administrative cost relative to amounts spent on programs. On the surface, this might seem logical, but it perpetuates the double standards discussed above. She argues it also has a particularly harmful impact on smaller charities who have a higher ratio of personnel costs to program costs than larger, more established organizations.

It’s Not All Bad for Non-Profits, But…

Non-profit have some benefits. Not having to pay taxes is great. Not having to provide any return on money to “investors” (a.k.a. donors) might seem advantageous on the surface. Additionally, there are some organizations that must be organized as non-profit entities for one reason or another.

Generally, however, the benefits of organizing as a non-profit entity pale in comparison to the list of opportunities for growth and development available only to for-profit enterprises.

We have the power to change this.

Social Innovation Changing How We Value Social Enterprises

We need to shift the paradigm about how non-profits are “allowed” to invest in their people and their missions. We continue to hold our non-profits to double standards relative to their for-profit counterparts, but we know now that this is not fair or sustainable. It’s time we orchestrate a change.

Pallotta says “If that can be our generations enduring legacy, that we took responsibility for the thinking that had been handed down to us, that we revisited it, we revised it, and we reinvented the whole way humanity thinks about changing things forever, for everyone… that would be a real social innovation.”

How Are We Evening The Playing Field?

We can begin by changing the narrative and better understanding the nuances of administrative and overhead costs necessary to run a successful non-profit organization. When analyzing the health and financial adequacy of a non-profit, review in greater detail the components of overhead and how the organization turned the overhead expenses into real dollars for the mission. Do we really care that overhead increases as a percentage of total revenue if net revenue, after expenses, catapults at a much faster rate and generates far more real dollars for the cause?

We also see the rise of a new type of organization that can help shift the conversation about financial support for social enterprises. B Lab, a non-profit organization dedicated to using the power of business as a force for good, is building a solution. They’ve married the social activist role traditionally filled by non-profits with the economic and cultural advantages of for-profit business by establishing a B Corporation certification.

B Lab established a set of rigorous standards against which companies are assessed in order to be classified as a B Corporation. The standards require a company to maintain compliance with various measures related to social and environmental performance, public transparency, and legal accountability while fulfilling a mission to use the power of the markets to solve social and environmental problems.

In short, the B Corporation certification brings together the best of both worlds for those of us looking to make the greatest impact on our world in the most efficient way. Companies have access to all of the benefits of being a for-profit organization while ensuring shareholders expect a social or environmental mission to be central to the company’s goals and objectives.

Support the B Corporations In Your Communities

More and more companies are becoming Certified B Corporations. Not only does this help ensure the companies can maintain their social and environmental missions but it also helps consumers trust that the companies are following through on their for-progress commitments.

This new certification, along with a growing understanding of the double standard to which non-profit organizations are held, helps us develop a better idea of how to fund and support the entities driving and striving for real and effective change in our world.

Next time you’re shopping, be on the lookout for the Certified B Corporation stamp of approval (or search through DoneGood, which has many Certified B Corps in their database). If you’re looking to make a donation to a charity, consider the importance of unrestricted donations. We must value investing in talented employees, promising long-term projects, and big ideas that can make or break the organization’s ability to achieve its mission, even if it goes by the ugly name of “overhead.”